9, June 2021

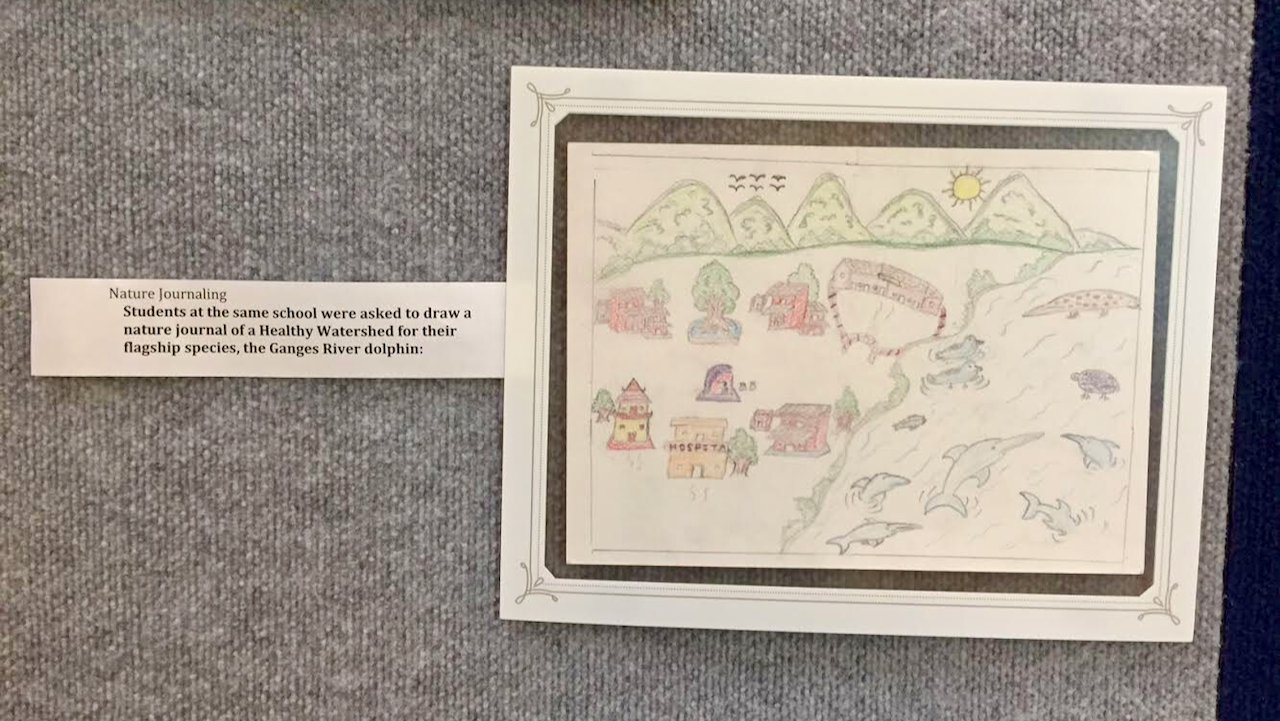

A child’s vision of ecology

1. There are river dolphins in Nepal.

2. Our sustainability coordinator, Sarah, is a published expert on them.

But this isn’t really a story about river dolphins. It’s about the incidental things that we learn about ourselves while we think we’re studying nature. And it’s a story we found so eye opening when Sarah shared it with us, we wanted to share it with you too.

Sunita Tharu is 12 and lives on Nepal’s largest island, Badalpur. Formed into a tear-drop like shape by the mighty Karnali river of Western Nepal, Badalpur is home to a few indigenous clans and surrounded by one of the most species rich zones on the planet.

Sunita’s family is Tharu, and fishing is an essential component of Tharu life. Many subsist on an abundance of fish, frogs and freshwater crustaceans provided by the longest river in Nepal — the headwater of which emanates 500+ km from Mount Kailash in Tibet, all the way down towards Badalpur in the lowlands on the border with India.

It takes Sunita 2 hours by foot, diesel ferry and local bus to travel to her school in Thakudwara on the Eastern border of the river. And it is there that part 1 of Sarah’s research project took place.

As part of the Ganges River Dolphin and Wildlife Conservation Project, Sunita and her classmates were asked to draw their visions of a ‘pristine and thriving watershed’.

Dolphins, eagles, elephants and rich biodiversity filled the children’s papers. But woven between them, all along the river channels, were buildings too. Hospitals, schools, fisheries, temples and homes. All of the places necessary for humans to thrive.

Half a world away, part 2 of Sarah’s research project took place in Georgia, USA. The children there were asked the exact same question. They too filled their papers with local wildlife: eagles, ospreys, alligators and beavers. But that’s where it stopped. There wasn’t a building in sight. Not a trace of the human element within the American children’s ‘thriving and pristine watersheds’.

So it seems we’re living in a world where children in ‘developed’ countries cannot even imagine living alongside a thriving ecosystem. It is not their fault, of course. They have just never seen it possible. Those two ideas have never coexisted in their lived experience. And yet, as the children in ‘lesser developed’ countries show us, it is the only way. It is a must.

As Sarah puts it: To return nature to its state of balance, it is fundamental that our new economy respects the limits of our planet’s resources, its functions and what is sustainable. A shift in our epistemological dimensions of learning is absolutely necessary.

(We think that’s a super smart way of saying that the dream of a thriving society opon a thriving planet is possible — if only because children like Sunita can imagine it).